December 2018

The review and approval process for the merger of Sprint and T-Mobile is moving along, with both companies optimistic that the deal will be closed in the first half of 2019. As such, there's no way to talk about the spectrum utilization of T-Mobile and Sprint without considering how the two companies will stand when their networks (and spectrum assets are combined).

Key findings

- Sprint leans heavily on 2500 MHz mid-band spectrum for its data capacity; even so, it has only built out a small proportion of its total holdings.

- Both companies utilize relatively little low-band spectrum, with only T-Mobile using its 700 MHz holdings for limited rural coverage.

- T-Mobile's limited mid-band holdings and rapid subscriber growth point to capacity problems in the future; without merger approval, the operator may face capacity issues.

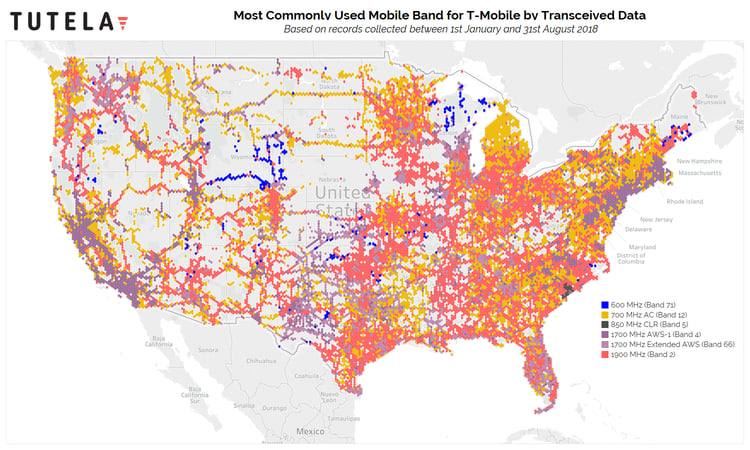

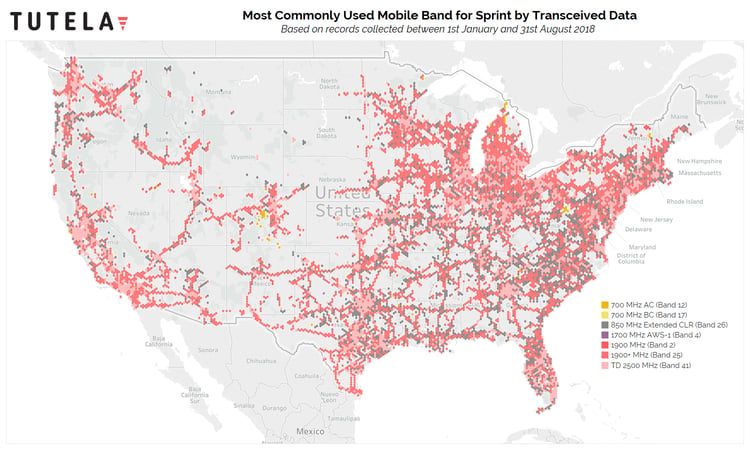

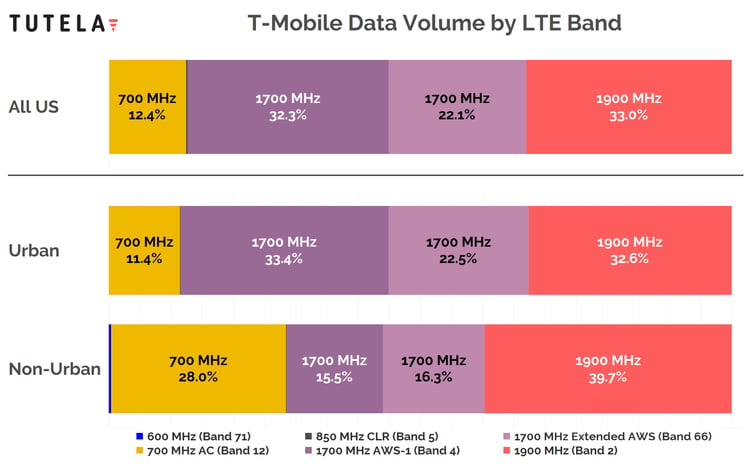

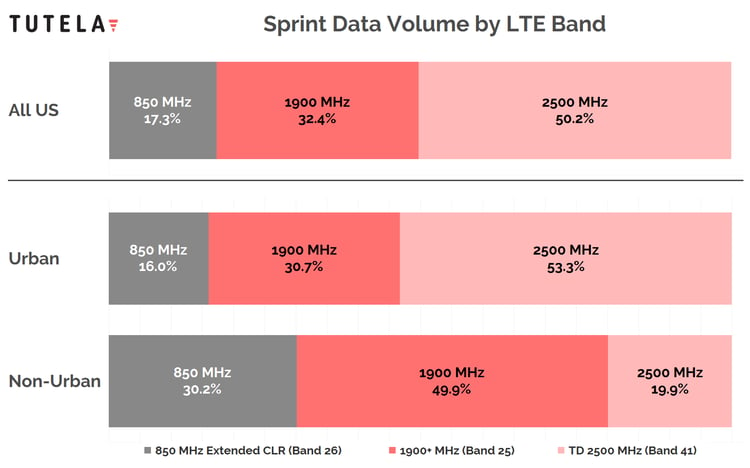

Tutela extrapolated information on data transfer volume and LTE bands from its dataset of hundreds of millions of tests nationwide, taken between January 1st and August 31st 2018. The maps show the most commonly-used LTE band by geographic location, broken down by operator, while the charts show the volume of data transferred by LTE band, divided between rural and urban areas.

In non-urban areas, both Sprint and T-Mobile transfer around 30% of their data over low-band spectrum, 700 MHz in the case of T-Mobile, and 850 MHz for Sprint. That volume is relatively low, especially compared to Verizon, which used the 700 MHz band for nearly 60% of its data transfer in non-urban areas.

The results speak to Verizon and AT&T's historical advantage with low-band spectrum holdings, which resulted in their modern-day advantage in rural coverage. Due to its RF propagation characteristics, low-band spectrum travels further and penetrates buildings better, which makes it better suited to covering wide geographic areas.

While T-Mobile now has some 700 MHz spectrum and Sprint has some licenses in the 850 MHz band, both providers have previously lacked the low-band bandwidth for truly high-capacity rural coverage. The New T-Mobile will be able to use the $8 billion in 600 MHz licenses that T-Mobile purchased in 2017, however, and which T-Mobile has already said will serve as the backbone of its nationwide 5G network.

Despite T-Mobile having to work around the analog TV stations that are still being migrated off the 600 MHz spectrum, the company has nonetheless built out its new low-band holdings at an impressive speed. However, Band 71 only accounts for a fraction of T-Mobile's total data volume currently; this is likely due to the relatively small number of 600 MHz-compatible devices within T-Mobile's customer base. Although the data volume barely shows up on this report, a look at T-Mobile's geographic spectrum map exposes how Band 71 is already the most popular (in all likelihood, the only!) T-Mobile LTE band in several sparsely-populated states, such as Wymoing -- which was also the location of T-Mobile's first Band 71 deployment.

With the impending shift to 5G, however, low-band spectrum is losing some of its status as the "beachfront" holding to have. Mid-band and high-band spectrum will be equally important as the challenge for operators shifts from coverage to capacity; it also shows that without the merger going through, T-Mobile could be in trouble.

The last few years have seen T-Mobile's growth explode; the company has grown from 49 to 74 million subscribers from 2014 to present, and it's added over a million subscribers in every quarter so far in 2018.

In the same time period, T-Mobile has invested only slightly in mid-band spectrum. Although it did purchase $1.77 billion of AWS-3 spectrum in the FCC's 2015 auction, its most significant spectrum investments in the last four years have been the $8 billion 600 MHz purchase, and a $3.3 billion purchase of 700 MHz spectrum from Verizon -- in which instance it actually traded away some mid-band AWS and PCS spectrum in return for the low-band holdings.

T-Mobile's reliance on its relatively limited mid-band holdings is observable in Tutela's data. Although T-Mobile holds a similar amount of mid-band spectrum as AT&T and Verizon, it leans on it much more heavily. On average, T-Mobile holds 69 MHz of mid-band spectrum nationwide; that 69 MHz carries 87% of T-Mobile's LTE traffic. By comparison, AT&T's 73 MHz of mid-band spectrum carries 53% of its traffic, while Verizon's 68 MHz of mid-band only accounts for 45% of total LTE traffic.

Assuming that T-Mobile's subscriber growth continues, the heavy utilization of its mid-band spectrum points to a capacity crunch in the future. While its investment in 600 MHz will be good for coverage, the average 31 MHz of Band 71 it holds nationwide won't provide a meaningful increase in capacity.

Worse, T-Mobile's limited mid-band and non-existent high-band holdings will make adding capacity through network densification challenging. Small cells are heralded as the key for adding capacity to a network, especially with 5G. The same propagation characteristics that make low-band spectrum ideal for rural coverage preclude its effectiveness for small cell deployments; mid-band and high-band frequencies are better suited for small-cell applications, as more micro cell sites can be added to an area without interfering with each other (or the macro cell).

This is where Sprint's spectrum holdings could come into play. Sprint holds nearly 80 percent of the licenses for 2.5GHz EBS and BRS spectrum, which equates to an average of 150 MHz of capacity in 2500 MHz nationwide. Sprint hasn't built that spectrum out fully, thanks to a lack of customers and capital, but New T-Mobile, with more customers and a budding 5G network, will be able to make use of the prime mid-band spectrum for a 5G network with better coverage than competitors relying on higher-band spectrum.

One thing that neither T-Mobile nor Sprint have in abudance, however, is millimeter-wave spectrum. Depending on the results of the FCC's ongoing auction, that might change; for now, however, New T-Mobile's 5G roadmap will be dictated by the spectrum it does have. The public focus for T-Mobile has so far been on deploying 5G that's "nationwide" and "mobile"; in practice, that means using its 600 MHz network, and likely Sprint's unused 2500 MHz spectrum assuming the merger is approved. Verizon and AT&T, meanwhile, are committed to 5G in millimeter-wave bands in the near future. The difference in networks and consumer experience is likely to be profound, which will set up some interesting public battles between the two approaches.

Discover more of our data insights for the United States, and across the world, by joining Tutela Insights today.